Students in the American Foundry Society Club at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville recently topped their previous successes in a regional casting competition by not only taking a first-place finish, but also earning the competition’s Imagination in Metalcasting Award – a first in the competition’s history. The team took home a total of $4,100 in award money.

The 2020 American Foundry Society Wisconsin Regional Casting Competition was held Feb. 13-15 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Eleven students attended with advisors Dr. Kyle Metzloff, professor of industrial studies, and Henry Frear, associate lecturer in industrial studies. The team competed against six other schools, including large programs such as Michigan Tech University and UW-Madison.

The team took a non-traditional approach to choosing a part to cast for the competition. After taking first place in the annual competition for several years, the students wanted to further challenge themselves this year.

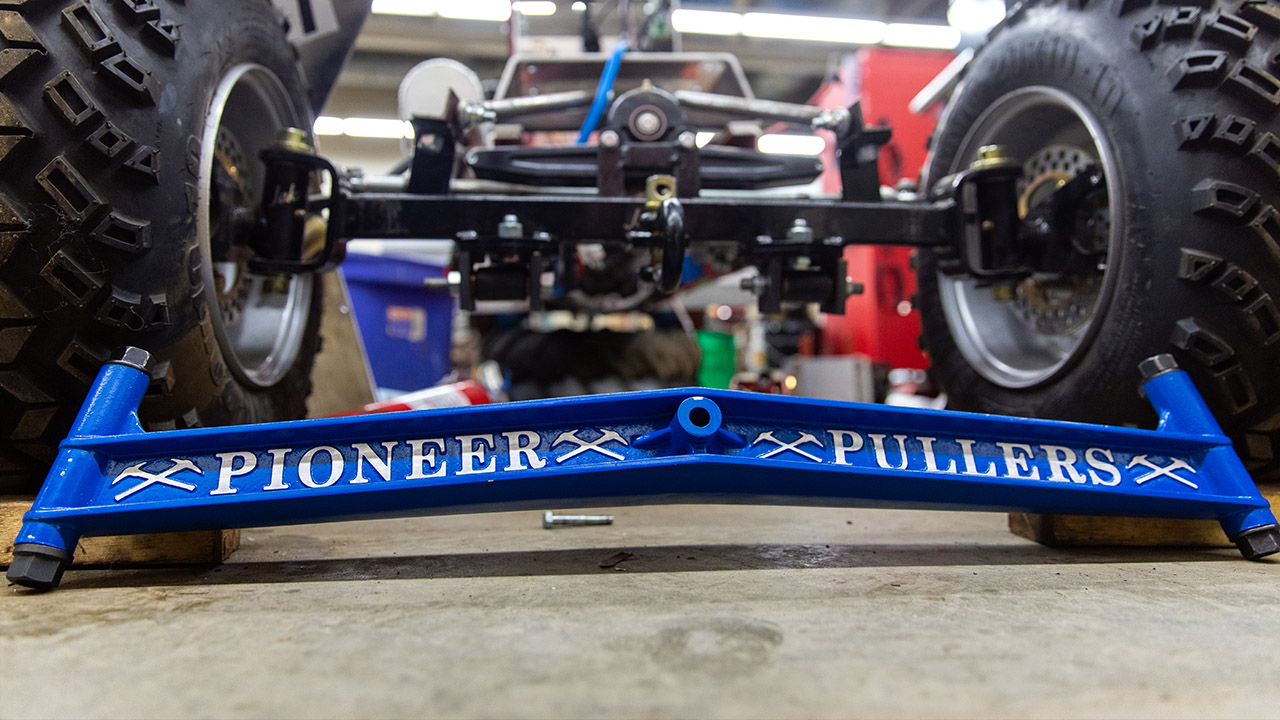

“We actually came up with a process we wanted to try first, and then went looking for a part based on that,” said Metzloff. The part they selected was the front axle of a one-quarter scale pulling tractor used by the Agricultural Mechanization Club.

According to Metzloff and Frear, the process they chose is one that has never been done before. It combines ablation — which is a relatively new process in the metalcasting industry itself — with ice molding. In the ablation technique, parts are cast in sand molds, and then quickly washed away with high power jets to speed solidification. In their process, the students used an ice mold binder with sand composed of silica sand, a low percentage of clay and a percentage of water. When exposed to freezing temperatures, ice crystals form as a binder in the sand.

“Ablation is a process used by Honda for their new Acura NSX, and they are one of the only production castings being made this way, and the first to do it in 2017, so it is very cutting edge,” said Frear. “When you put the two together – the ice mold and ablation – that has never been done before.”

It was this original process that earned the team the Imagination in Metalcasting Award, which is given to the project that exhibits innovation in processing, materials or post processing; reduces environmental impact of metalcasting; or has a potential impact to the industry within the lifetime of the student.

“When they called the students up to receive this award, I believe [the judges’] exact words were that they checked every single one of the boxes,” said Metzloff.

The students began preliminary planning for their project during the fall semester, but did not start any physical work in the lab until the first week of January, giving them only six weeks to perfect their entry. As a team, they spent more than 1,000 person-hours on the project during that period. They frequently poured two molds a day. Because the process required them to wait 12 hours between pours for efficient freezing time, they often completed one in the morning and one in the late night.

“I am very impressed with the amount of effort students put in,” said Metzloff. “This was not part of a class, it was all voluntary.”

As expected with a complex, new process, many challenges arose that required quick problem solving.

“There were a thousand problems to solve that we didn’t even know were problems yet, on January 1,” said Frear. “We had no idea what was going to go wrong or right.”

One of the issues to contend with was unseasonable warmth in January, which required making adjustments to their molds and securing a deep freezer so they could continue on schedule.

“We were also a little worried about our gating,” said Andrea McDermott, a member of the competition team and a senior industrial technology management major from Platteville. McDermott explained that the gating is essentially the flowpath in a mold in which molten metal is poured to fill the mold cavity. “We used a newer style gating. Normally, with a part this big, even seasoned professional would think that gating this small wouldn’t fill a part like this without freezing off at some point. We did the math, and it worked.”

“In the metal casting industry, it takes weeks or months to make a pattern, and usually costs thousands of dollars,” said Frear.

Metzloff agreed, adding, “Between our 3D Print Lab and some handy skills, our students can produce really good tooling for about $40, and do it faster.”

The students worked with John Deere in Moline, Illinois, to load test the part.

“We calculated for a certain amount of force, because of what the tractor would go through during its trials – if it does a wheelie, comes crashing down or hits an obstacle,” explained McDermott. “We ended up doubling our expected force before we even reached our yield strength, which is when the part takes a permanent bend. Our calculated yield strength was 2,700 pounds based on a conservative estimate from the limited data available for ablated aluminum castings. The yield ended up being 6,000 pounds, and we actually reached 8,500 pounds before reaching the travel limits of the test machine. We well exceeded the maximum of what we needed to be at, and we didn’t even break our axle casting, which is the most amazing part.”

According to McDermott, a large factor in the team’s success, was the ability for students from different disciplines to come together.

“To join the American Foundry Society Club, industrial studies or metals doesn’t have to be your major or minor; it’s a way for people of different backgrounds to come together, and in this project it was vital,” said McDermottt, adding that she brought plastics experience and did 3D printing and tooling work, while others had ag industrial tech, metals, mechanical engineering, controls, electronics, and fabrication and machining experience. “It takes all kinds, and to get to see all of that come together and everyone contributing in their own way is fantastic. You can’t get that anywhere else.”

This competition is one of many opportunities in the Manufacturing Technology Management program that offer students experience that gives them an edge when they enter the workforce.

“When you talk to industries, something that sets our program apart from everyone else is the hands-on experience,” said McDermott. “What people don’t always think about in their college education is that it’s not always the theory, but also the practice, and this program provides both. It’s funny because we’re pretty small at the university, but when you go out in industry or to a regional conference, everyone knows who we are [the American Foundry Society Club]. We have a great reputation for students, and to go out there knowing that is great.”

Frear agreed, adding, “Our students from this program are highly sought after, especially in the foundry industry, because of that mix of theoretical and practical, they can hit the ground running. Other programs may have theoretical experience, but it takes years of employment at a foundry to get up to speed, and it’s really hard to find the time to learn that stuff while you’re employed.”

The career outlook for students is good, according to Metzloff, who said graduates of the program who want to work in a foundry have a 100% placement rate, with some of the highest starting wages of UW Platteville graduates, and Wisconsin is among the top three states in the country for the size of the foundry industry.

A lot of this, McDermott said, is attributed to the faculty in UW-Platteville’s Manufacturing Technology Management Program.

“Henry and Kyle are some of the best professors you could ever ask for,” she said. “They give up their time for our projects and push us to do our best. We would never get this far without them giving us those high expectations, but helping us along the way. There are just no words to express everyone’s gratitude for them.”