The Sauk Prairie Recreation Area, on the site of the former Badger Army Ammunition Plant between Baraboo and Sauk City, includes a 4,500 acre prairie restoration, with ambitious goals to remove woody plant species, and repopulate native prairie grasses and other plants. An important way to measure the success of the ongoing restoration is to track and learn about the local rodents that are drawn to the changing landscape. That’s where the work of Baraboo Sauk County students Zac Larson and Myjah Drews comes in, as they work to identify the species of juvenile field mice that are making their way back to the recovering prairie.

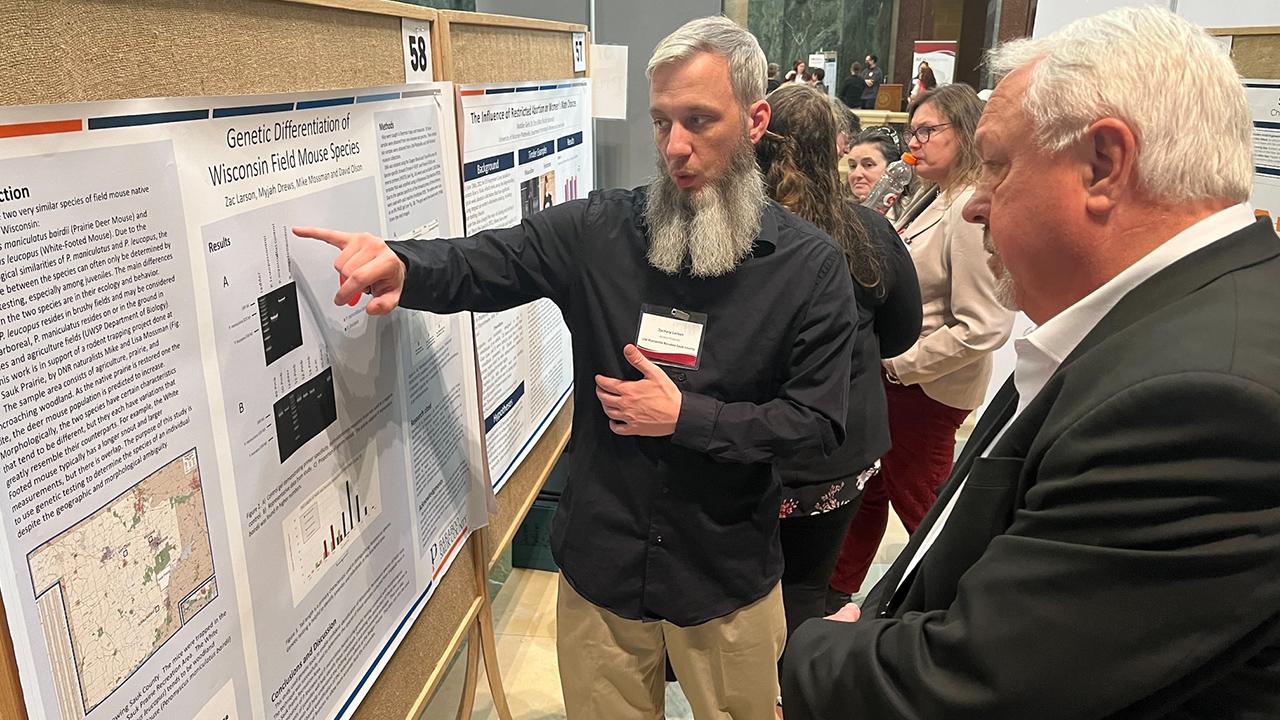

Larson and Drews presented their findings and other observations about the progress of the prairie restoration to legislators, state leaders and peers from across the UW System at the 19th annual Research in the Rotunda on March 8 in the state Capitol.

Through the use of the campus’ lab equipment, and techniques of genetic identification they are learning from Biology Professor Dr. David Olson, Larson and Drews have checked the identities of scores of mice, searching for two types, the white-footed mouse and the deer mouse. The white-footed mouse prefers the pre-restoration woody landscape, while the deer mouse is drawn to the recovering prairie. By identifying the two species, and their shifting populations on the land, Larson and Drews are contributing important data to the ongoing work of area naturalists leading the restoration.

Larson is a business major, but was drawn to the science project by its importance to the local area, by Olson’s enthusiasm, and by the chance to understand and gain experience with the lab work and lab techniques that are critical to the success of any scientific enterprise.

“I think the economy and the ecology are going to be more and more intertwined,” said Larson, who described the multi-step PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) process of genetic identification that he and Drews use to see which mice are returning.

After receiving a tiny fur sample from the mouse’s ear, the students use an enzyme and a filtering process to extract DNA. Then, using other equipment and skills at the campus, they match the base pairs from the sample with unique markers from each mouse species “to see who we’re dealing with,” Larson said. In the first week alone, Larson and Drews were able to test hair samples from 69 different juvenile mice that the field naturalists captured, and they have continued to test more samples throughout the fall.

This work genetically identifying the mice coming on the recovering prairie provides important confirmation for the broader data that naturalists in the field are capturing, said Olson, who plans to use the ongoing project to train future students in these lab techniques. “That’s an exciting ongoing opportunity for students at this campus.”

The work will also provide critical support for the ongoing restoration project.

“What’s exciting there is the way we can use the genetic identifications to find other correlations, like tail length and other characteristics, that will let even more species identifications happen in the field,” said Olson. “That leads to richer data, and that will be an ongoing help to everyone working so hard to grow and maintain this recovering natural area.”