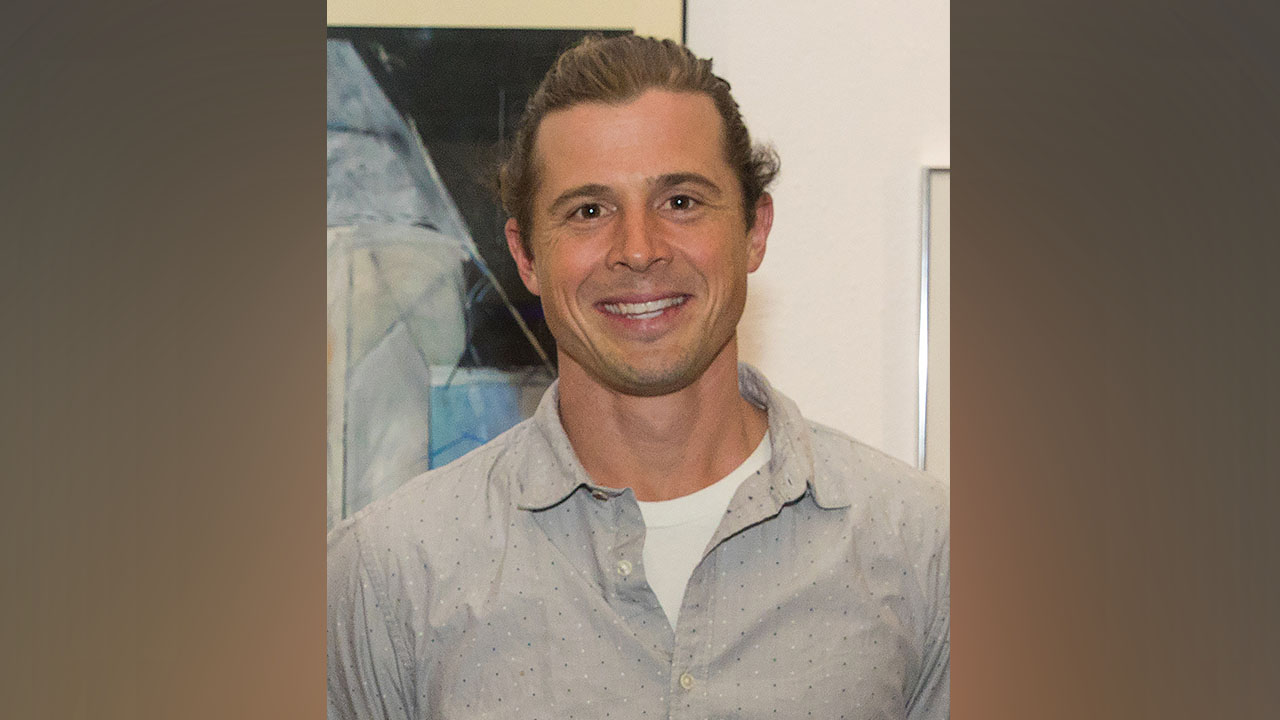

Dr. Evan Larson, professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, and his collaborators have been paddling the lakes of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness for the past 15 years to conduct a sprawling research project. Initially focused on finding old trees to provide perspective on past climate, the work developed into a career-defining project better understanding the relationships between people and historical fire regimes with implications for fire management in the United States, the perception of wilderness and social justice around Indigenous land use practices and traditional practices. After years of building upon their research, Larson; Dr. Kurt F. Kipfmueller, associate professor of geography, environment and society at the University of Minnesota; Lane Johnson, forest research specialist at the Cloquet Forestry Center and Dr. Elizabeth Schneider, instructional designer at Sacred Heart University, have co-authored, "Human-augmentation of historical red pine surface fire regimes in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness." Their paper has been published in the journal Ecosphere.

“The timing of this publication falls in the midst of a pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement, which is driving conversation about equity, justice and history around the world. It’s important to realize this project is engaged in that same conversation in the sense that it’s looking at land and systems that have this important cultural legacy and that modern concepts of wilderness essentially eliminate that,” said Larson. “If you think about the implication of that act, it’s enormous. With the publication we have quantitative data to go along with the oral history and cultural knowledge that are helping to shape the narrative and the conversation around this issue; it’s a big deal.”

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is located in northeast Minnesota and lies within the Superior National Forest. The area includes more than one million acres and extends 150 miles along the U.S. and Canada border, according to the United States Forest Service.

The Boundary Waters is rich in history and received protective status from the U.S. government decades ago, creating the opportunity for Larson and his colleagues to examine the landscape through the lens of tree-rings and fire scars. The fire scars preserved in the rings of ancient trees and stumps helped Larson understand patterns of fire activity over the past five centuries.

“We have these old living trees that provide an incredible record, and the stories from these trees can be linked with the human stories written across the land,” he said. “There are numerous Anishinaabe communities with deep connections to these lands, and their cultural history is very much present in that space. They still carry these stories that connect them and their ancestors to a lot of these specific points. Written records left by early European explorers and fur traders also provide insight to the history of the region. That kind of confluence of factors and evidence are rare.”

Although some historical fires burned hot like those shown on modern news reports, the research team documented the continuous occurrence of low-severity fires that instead of burning down a forest, maintained an open, park-like forest that made travel easy. These were forests created through fire, not destroyed.

“We could see patterns connecting people to fire in the past, and realized these same places are now the favorite spots of modern day (wilderness) visitors,” said Larson.

The topics of fire management and social justice around Indigenous land use practices need to be discussed because they are interwoven according to Larson. He notes to start this difficult conversation it takes time, trust, communication and the willingness to be wrong.

“If we only talk about one aspect of it – the numbers or data – it’s a disservice to the complexity and richness of this place and time,” said Larson. “It’s perpetuating the status quo and how science has been done for so long, where we brush away the things we don’t talk about because it makes it complicated, emotional and it starts to undermine the notion of scientific objectivity.”

One of the most powerful lessons Larson received throughout this project has been communicating with elders in Indigenous communities and learning how in some cases stories regarding fires have been eliminated.

“Those stories were broken through a generational gap caused by allotment, boarding schools and policies meant to erase people and cultures,” he said. “These trees, in a way, have carried the stories that span that gap and are helping people remember. To be able to serve in that role of translator of stories that are carried from people to trees and now back to people; it’s a magical side of this whole effort. It touches on the profound and it moves me. It’s been an absolute honor to be able to play any role in this.”

As discussions emerge, Larson hopes the paper can serve as a touch point with fire serving as the common cultural factor.

“What we have done now is taken this project, which has become deeply intertwined with a lot of community-based conversations that are really connected with this current moment our entire society is in, in terms of pausing and reflecting on our history, both the good and the bad, the dark as well as the beautiful, and having an honest and truthful conversation with ourselves and everyone around us,” said Larson. “Hopefully, it will help us walk forward collaboratively, truthfully and engage with a lot of healing that needs to happen, with people and the forest.”