Amid a decades-long trend of declining bird populations in North America, setting land aside for preservation has long been a primary approach to protect biodiversity. Dr. Lynnette Dornak, associate professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, researched the effectiveness of this method, and her work, “Assessing the Efficacy of Protected and Multiple-Use Lands for Bird Conservation in the U.S.,” was recently published by the scientific journal, PLOS ONE.

Dornak, and her research team, studied two categories of land – protected and multiple-use land. Both land designations are managed to conserve biodiversity, but with different levels of protection. While protected land has an explicit goal of preserving biodiversity and ecosystems, multiple-use land shares this goal – as one of many – and can be managed for extractive uses, such as logging, grazing or energy development.

“The difference between the land use is similar to the difference between preservation and conservation,” explained Dornak. “Preservation means that we preserve the land for what it was and should be, and we have minimal use on it. National parks, for example, are protected areas – we use them, but they are really concentrated on biodiversity. In multiple-use lands, we still want to protect biodiversity, but we are more focused on conservation. We’re still not turning them into a strip mall, but they can be used for things like grazing cattle, mining and harvesting timber.”

While past studies have sought to evaluate the efficacy of protected and multiple-use lands in conserving biodiversity, they focused primarily on the equal representation of species on these lands. Dornak’s research aimed to qualitatively measure the impact to these species.

“When you look across different types of protected and multiple-use lands, you can’t just look at what species are equally represented on all of them, because species use things differently, and at different times of the year,” she said. “So, you have to determine not how many species are using the land, necessarily, but what is the qualitative impact on those species.”

Dornak selected birds as the species to study, as they are an overall good indicator of environmental health, responding quickly to disruptions in their environment.

“Birds respond really quickly, because they are mobile,” said Dornak. “They are either going to use the land or not use the land. Birds can also be very particular. When we look across unique environments, there are birds associated with those that are pretty specific in their needs. Also, birds are easily counted. They are easy to see and hear without having really special equipment.”

Dornak and her team completed the research between 2013-14, using data from the U.S. Geological Survey, including its North American Breeding Bird Survey. Dornak concluded, through the research, that relying on protected lands, alone, is not sufficient for maintaining biodiversity.

“The idea of preserving biodiversity is bigger than just designating protected land,” said Dornak. “We have to consider those other lands. To some extent, birds are using multiple-use lands as much or more frequently, or in a different way, than protected lands. A lot of our protected lands are surrounded by agriculture or human development, and that changes the preserved area. We need to consider what is adjacent to preserved areas. We have to look at it all as a whole with a more holistic perspective.”

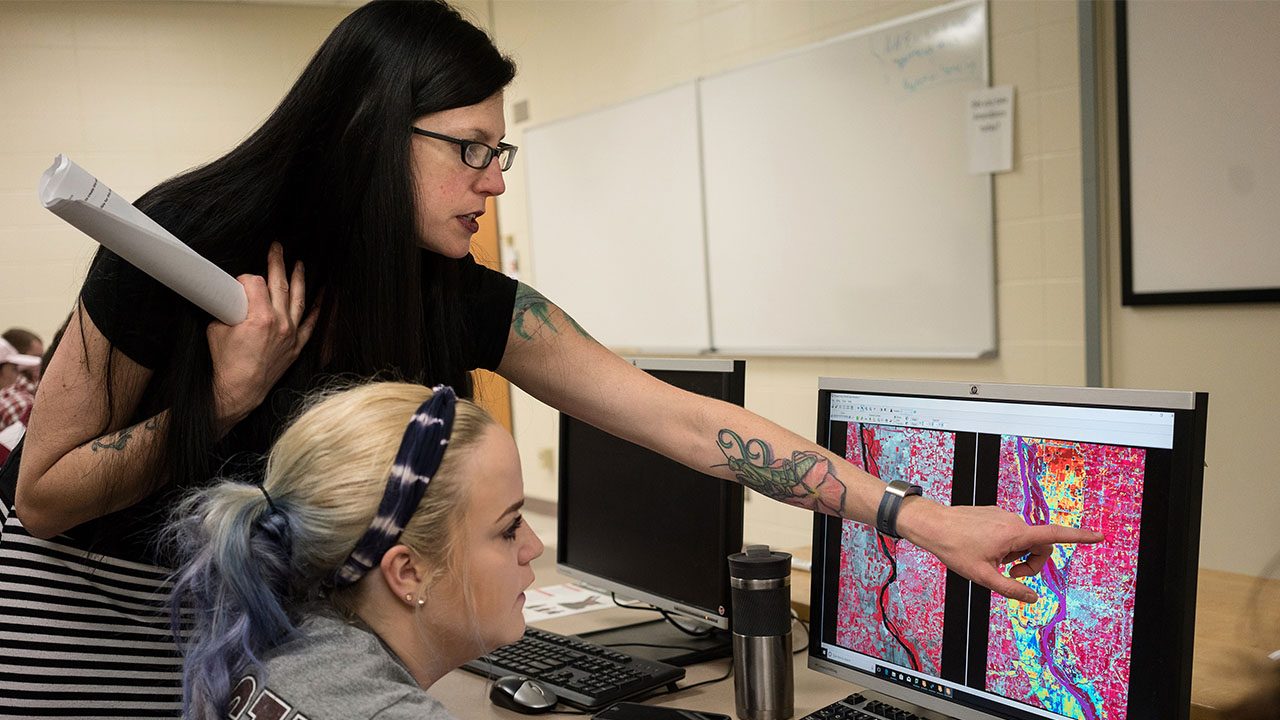

Dornak plans to incorporate the research in some of her classes at UW-Platteville, including the Planet Earth course and her GIS courses, in which students can work with portions of her research data sets. She will also be teaching a special topics course on landscape ecology in the spring, which she said will be a natural fit to explore this topic.

Dornak said she hopes publishing this research will bring more awareness to the issue of declining bird populations.

“We are seeing this continual decline in our species, because we keep dividing up and fragmenting their habitats,” said Dornak. “I hope people see that, while protected areas are definitely important, there is utility in some of these multi-use lands.”