Watching students develop their own artistic voices, demonstrating the value of physical creation and facilitating an environment that stresses the importance of failing, sharing and community are what Scott Steder treasures most about teaching.

Steder, a lecturer of art at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville since fall 2017, teaches courses in sculpture, drawing, professional practices and all levels of ceramics. He was first drawn to the field of art in high school, when he took a ceramics class, and he never looked back. Some of his favorite memories of creating art as a youth and young adult include creating lifelong relationships with fellow studio artists and professors and building kilns in graduate school, both on campus and in Paraguay for the 1st International Biennial of Asunción, a cultural, artistic and social project organized by the Asociación Bienal de Asunción.

Steder received an Associate’s in art from William Rainey Harper College in Palatine, Illinois, in 2009. Shortly after, he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in ceramics from Northern Illinois University in DeKalb and a Post-Baccalaureate from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Following his time in Knoxville, he was accepted as a year-long artist-in-residence at the Cub Creek Foundation in Appomattox, Virginia. In 2017, after his residency, Steder earned a Master of Fine Arts in ceramics from Wichita State University in Kansas.

Since his time at Northern Illinois University, Steder has shown his work across the United States, including the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts’ National Student Juried Exhibition in Providence, Rhode Island, and “Beyond the Brickyard” at the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena, Montana.

Steder currently lives in Platteville with his wife, their son, and stepson. All four love to incorporate creativity and art into their home life. For example, they use handmade pottery and spend time drawing and painting together.

What do you love most about teaching and your students?

I love watching students grow and develop their own artistic voices. Every year or few years, I will get a few students who truly have passion. It really is something special to watch and help facilitate their growth. Those students bring an energy and life into the studio that is essential to a healthy workspace for everyone.

I love watching them share ideas and engage in conversations outside of class time; it really shows me they care. I am very impressed with the way my students push each other to be better artists. It’s exciting to see their willingness to experiment, and for being unafraid to fail. If you want to be endlessly motivated, failure is key.

Three things I hope students take away from my classes are work ethic, healthy competitiveness and a strong sense of intentionality. Everything they do should have reason and consideration, and they should be able to defend those decisions. The more competitive the studio, the harder they work and the stronger their bonds become.

How has the transition to alternative delivery teaching affected hands-on learning opportunities in your spring courses?

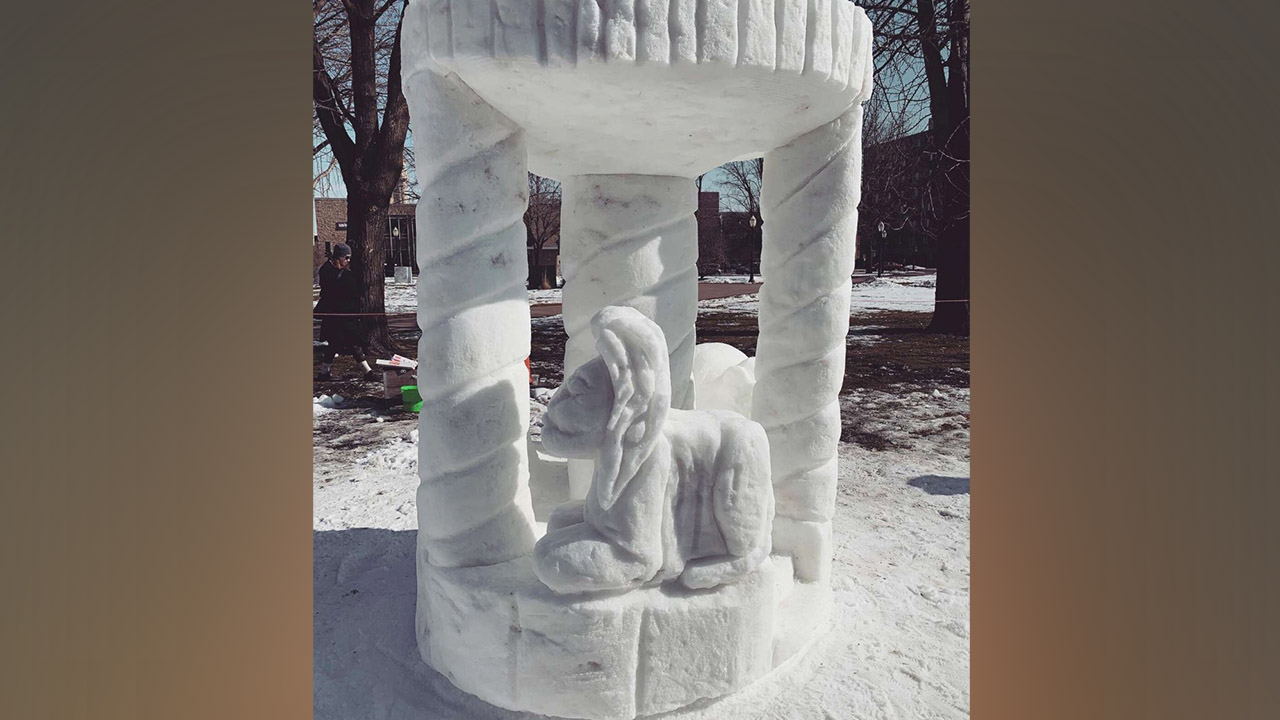

Although our hands-on work was cut short this semester, we packed a lot into the first half. One class I would like to highlight is my Public Space and Public Art class. We started off the semester by carving two 10-foot snow sculptures for the Dubuque Museum of Art. (To view a Telegraph Herald video about the project, visit: https://youtu.be/eRWQY1maN8w)

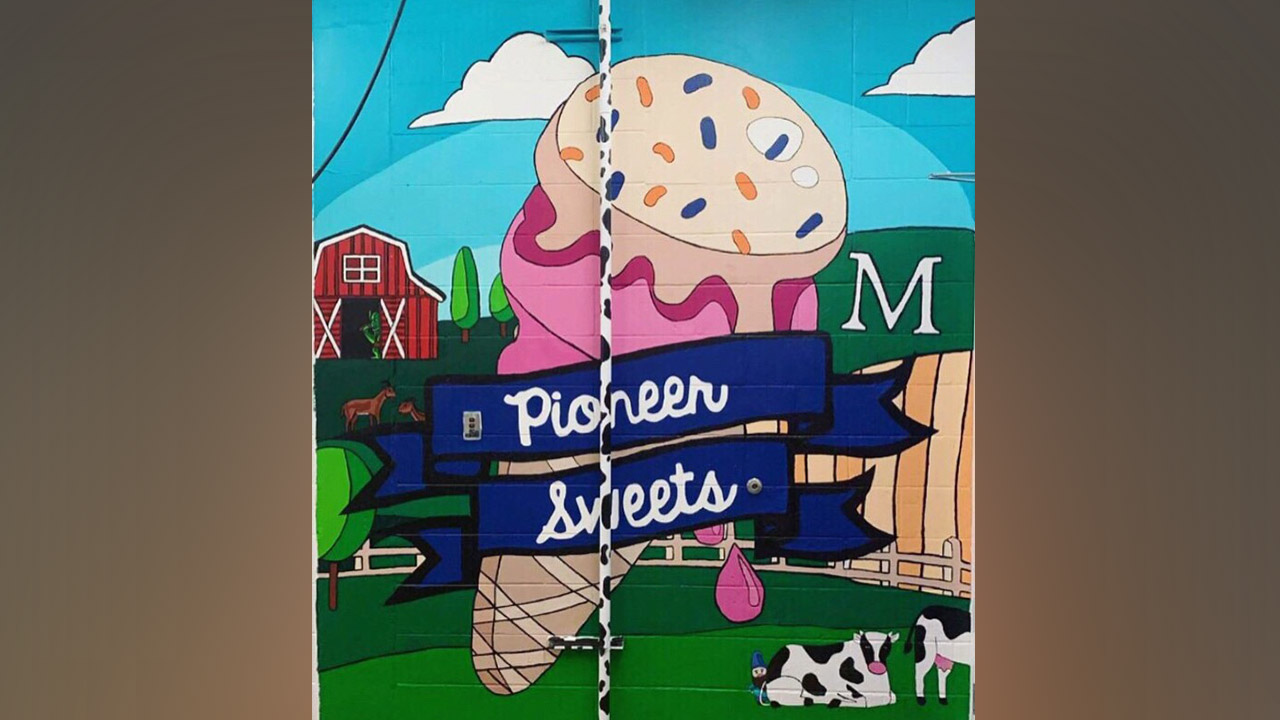

Following that project, we worked with Dr. Tera Montgomery, professor of dairy and animal science at UW-Platteville, to paint a mural in the university’s Glenview Commons. My students worked very hard on the design, and on March 2, we finished the 10-foot-by-11-foot mural.

To finish the semester, we would have been painting a 100-foot mural on the wall outside Badger Brothers in Platteville and another smaller one for UW-Platteville’s Student Health Services. These projects will still take shape in the future.

The transition to alternative delivery has affected hands-on learning opportunities in my spring courses by not being able to work directly with students. I allowed students to bring home clay and tools, and they have been sharing work done at home on Canvas. It’s nice to critique the work, but not being in the studio puts a damper on the creative process. The ability for students to problem solve with myself and one another is a huge part of that process.

The Public Space and Public Art class students are still designing from home, but without being able to do the actual painting, we have resorted to more research-based projects and are getting feedback from our clients about the designs. It’s a real bummer for myself and the students, but in these times, we just have to adapt. When we return to face-to-face instruction, I think everyone will be more grateful for the facilities and time in the studio.

In fall 2017, you initiated the first annual Empty Bowls project. Can you explain the project and how it helps create stronger bonds between the arts and the community while raising awareness to hunger and an appreciation of the arts?

Empty Bowls is an international grass roots movement that began in the early 1990s. A ceramics studio will create as many bowls as possible. They will then be sold at a set price. Included in your purchase, you get soup or chili, and after the event, your bowl is washed for you to take home. This bowl serves as a reminder of all the hungry people in the world. All the money raised is donated to a local food pantry. The food is donated by participants and local restaurants. We have a chili competition with prizes and raffles for people that attend the event. The prizes are pieces of art made by students and faculty, and generous donations from local businesses.

Ceramics is all about sharing information and creating a sense of community. I’ve been a part of quite a few Empty Bowls projects and it really is something special to see it all come together. Our third Empty Bowls project would have launched on April 5, but we had to reschedule it for the fall.

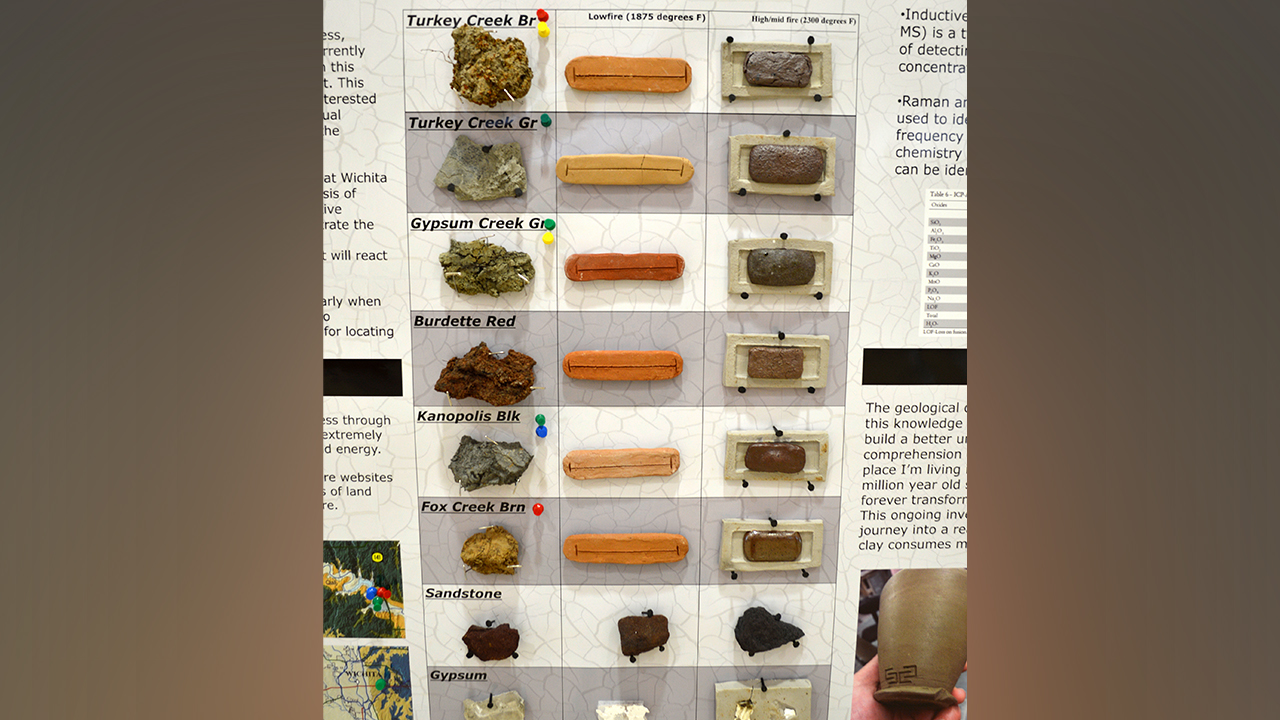

In a forum you presented on synthesizing the ceramic arts and science, you demonstrated the value of the ceramics process as a tangible learning tool, as well as its ability to contribute to environmental science. Can you expand on this?

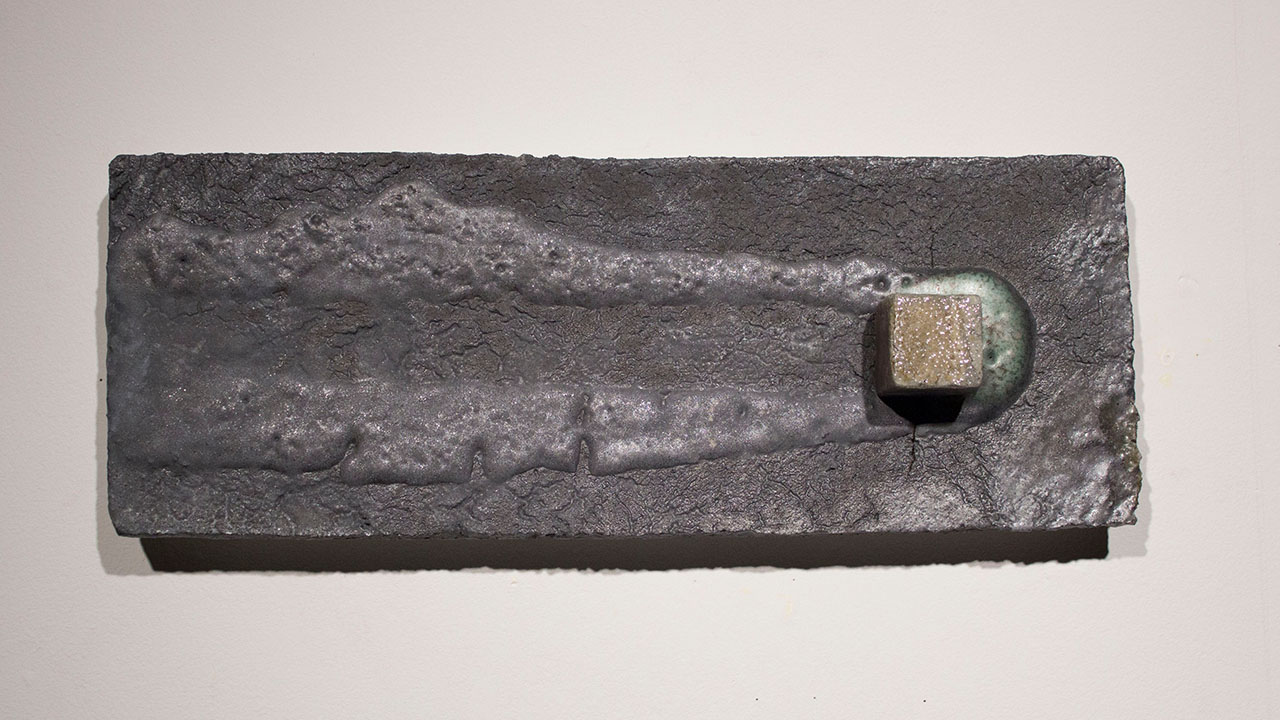

The ceramic process has so many applications. It’s such a vast media that, unless you took multiple years of classes, you would only be scratching the surface.

In the beginning ceramics classes, I stress problem solving and repetition. It’s very methodical and teaches a lot of discipline. I think it really appeals to engineers, given their ability to work with physical objects and witness material transformation. There is a lot of cause and effect.

In Ceramics 2 and Advanced Ceramics, we study the chemistry of glaze and clay body formulation. Students can create their own recipes and mix them using raw materials. We also get into applied thermodynamics when we build and fire kilns.

When we talk about environmental science, I think about how we could collaborate with the other fields. I look to kiln building, cooking applications, brick making and water filtration. I look for ways we can collaborate with other fields and groups like our environmental sciences, sustainability and renewable energy and Engineers Without Borders.

What do you most enjoy doing when you are not teaching?

I love to cook. If I were not a teacher, I would be a chef. The experimentation, aesthetics, transformation and community that goes along with culinary art inspires me. A chef I worked for years ago helped form my decision to pursue clay. He said, “Food will always be there, and people will always need to eat.” I love being able to cook nice meals for my family and it’s pretty fun to have all handmade dishes from which to eat and drink.